Честертон об Эдварде VII, 1910 - высший пилотаж etc.

wyradhe — 30.03.2017

Честертон об Эдварде VII, 1910 - высший пилотаж etc.

wyradhe — 30.03.2017

Честертон об Эдварде VII, 1910 - высший пилотаж etc.1. Etc. Предлагаю консолидированное определение: люди с рукопожатными лицами.

В ближайшем посте я - на примерах обещаний Навального касательно лезгинки, а также его выступлений по поводу согласия Путина на выборы Собянина в 2013 и недоведения до него мэрией предложений об изменении места демонстрации в 2017 - рассмотрю характерную общую черту "режимаТМ" и "оппозицииТМ" - так называемое вранье (в данном случае, т.о., на примере оппозицииТМ - на примере Киселевых это и так всякий может), а пока замечу, что по наблюдению А.Бабченко, "на все протесты властям по-прежнему абсолютно плевать и они их совершенно не боятся. Как и всегда" (http://starshinazapasa.livejournal.com/973741.html). И вот тут я как раз власть понимаю. Если бы директором был я, я бы тоже не боялся. Вот чего бы я боялся, - это если бы Зина и Дарья Петровна, обычные граждане - пролетарии и научные сотрудники - начали бы пачками подавать в мэрии заявки на массовые мероприятия на дюжину - три дюжины человек (подающий и его приятели и гости) в каких-нибудь парках за городом или где назначат в черте города, - уж ежели готов протестовать, так и до МКАД доехать можно потрудиться, и даже, страшно вымолвить, перейти за МКАД. И без всяких качаний прав за место, учиняемых только для того, чтобы был-таки конфликт и обидки, идут туда, куда скажут в доброй мэрии. И сколько таких мини-массовых мероприятий ни будет - всем придется искать место; а как они все вместе будут смотреться со стороны, и как на них люди будут налаживать связи и выдвигать кого-то из своих же, а не бегать за назначенными главоппами, - один Аллах ведает. Вот это мне было бы неприятно (главоппам тоже здорово не понравилось бы, впрочем), а то, что граждане исключительно тогда в массовку собираются, когда им накроет полянку Навальный, Явлинский и прочие, - это бы меня настолько не пугало, что я бы записи этих массовок крутил бы себе за завтраком для смеха и аппетита. Впрочем, у действующей власти чувство комического, кажется, отличается от моего.

2. Теперь к сабжу. Честертон об Эдварде VII, 1910 - высший пилотаж.

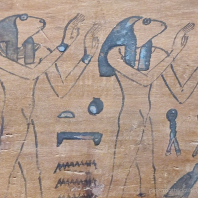

В мае-июне 1910 Честертон опубликовал, по горячим следам cмерти Эдварда VII, два эссе о нем в "Иллюстрированных Лондонских новостях". Эдвард был человек необычный и литераторами вниманием не обойденный: лорд Грей им восхищался (http://wyradhe.livejournal.com/90297.html), капитан Кэппел - трудно по-русски точно определить его родственную связь с королем, определенный тип связи есть, а термина нет [у чукчей, возможно бы, и нашелся бы], - тоже восхищался (http://wyradhe.livejournal.com/89796.html), Стивенсон - тоже восхищался (принц Флоризель - это как раз он, тогда еще Принц Уэльский), Киплинг его издалека недолюбливал, но посмотрев на его дела, проникся к нему величайшим уважением и восхищением и написал о нем по его смерти так панегирически, как разве что Чехов писал о Пржевальском, а сам Киплинг _так_ больше не писал ни о ком - ну, может, о Теодоре Рузвельте; Золя вывел его в "Нана", Конан-Дойль - в "Скандале в Богемии", Толстой - как принца-говядину в "Анне Карениной", см. http://wyradhe.livejournal.com/507927.html?thread=18232343#t18232343 (ну, понятно, как ЛНТ должно было корчить от Альберта-Эдварда; кстати говоря, тот даже заниматься любовью умел так, что его женщинам это нравилось, о чем он, собственно, заботился - и общеизвестно было это настолько, что заработал он себе пародийное прозвище Edward the Caresser (http://www.dailymail.co.uk/home/books/article-2251197/EDWARD-THE-CARESSER.html , https://discovermedicallondon.com/2014/07/02/edward-the-caresser-gentleman-addict-and-almost-by-accident-rather-a-fine-king/ и мн. др.); - в то время как манера самого ЛНТ в этой области закономерно породила у С.А-ны стойкое отвращение к явлению как таковому, - см. хоть уморительное, но ценнейшее по содержанию сочинение Жданова "Л. в ж. Л.Т.", http://litena.ru/books/item/f00/s00/z0000034/ ); певца культуры труда, дисциплины, самопринуждения к лишениям и преодоления боли, Эрнста Юнгера, от Эдварда корчило едва ли не сильнее, чем Толстого ( http://wyradhe.livejournal.com/76063.html).

Перед Честертоном задачи стояли сложные: он Эдварда, что и естественно, не переносил (http://wiradhe.livejournal.com/26798.html?thread=727470#t727470 и далее по треду; http://wyradhe.livejournal.com/53918.html). Однако выражать это не то что открыто, а сколько-нибудь полуприкрыто в 1910 году в газете было бы попросту самоубийственно: каким бы эксцентричным мудрецом-буффоном Честертона ни почитали, но уж тут добру молодцу в общественном мнении - точнее, во мнении той части общества, что была для Честертона существенна, - пришел бы конец (да еще и не напечатали бы). Поэтому он решился избрать иной путь: сказать о покойном много, много хорошего, чтобы самом в конце изящным пируэтом указать, что даже и в этом, лучшем своем образце, мир бездуховной буржуазной цивилизации, стал быть, сугубо бездуховен и ненароден, от истинных ценностей отделен непреодолимой пропастью, и до них падшей Европе еще только предстоит вновь подняться, если осилит, конечно. Кроме того, по тексту там и сям Честертон разбросал некоторые свои мысли в более ясной форме:

- то намекнул, что покойный король не заслуживал популярности, хоть она у него и была (в такой форме: even one who doubted whether the King deserved his popularity would be forced to admit that he had it),

- то дал понять, что была эта популярность вульгарной (King Edward’s popularity was such a very popular kind of popularity that it would be rather more appropriate to make his funeral vulgar than to make it aesthetic),

- а равно и недостойной по своей природе ( His popularity in poor families was so frank as to be undignified),

- а сам король был уж таким пошлым дюжинным обывателем, что в его честь нельзя было бы делать ничего даже самого прекрасного, будь оно хоть чуточку недюжинным, виноват, эксцентричным (King Edward was not the kind of man in whose honour we should do even beautiful things that are in any sense eccentric);

- а то уж прямым текстом написал, что мессианские призывы кайзера Вильгельма обоснованны, да вот бездуховная Европа их слышать не желает, а вот королю Эдварду, с его светским лоском, в рот смотрела (это потом Честертон возненавидел беднягу кайзера по самое все), и т.д.

Весь характер эссе можно в один присест усмотреть из того, что автор приписывает покойному королю "такт, умение себя вести и человечность"... и прибавляет, что все это король являл по всем конным бегам и гостиницам христианского мира ( Tact and habit and humanity had in him their final exponent in all the Courts, reviews, race-courses, and hotels of Christendom).

За всем тем Честертон не может отрицать, что король был всенародно любим и уважаем [причем и не из-под палки, и без Киселевых, и без всякой возможности петроIпочитаний, лениносталинопочитаний, путинопочитаний, ельцинопочитаний, навальнопочитаний, гайдаропочитаний и окуджавопочитаний у англичан 1900 года - "нет, здесь это не пройдет, не пройдет и не проедет, где угодно, но не здесь, - не пройдет никак!", http://wyradhe.livejournal.com/55671.html] и принес нации тьму пользы. Вот сочетание этого с истинными чувствами ГКЧ к покойнику и придает данным эссе невыразимую прелесть.

Эссе эти републикованы на бумаге были в 1987 в полном виде, а еще раньше, в 1955 году, были опубликованы Дороти Коллинз, секретаршей Честертона (в: The Glass Walking-stick And Other Essays). Эта публикация, в отличие от публикации 1987 года, выложена в сети: http://www.cse.dmu.ac.uk/~mward/gkc/books/The_Glass_Walking_Stick.txt

- но в публикации Коллинз оба эссе даны в поразительной форме. Впечатление такое, что Наталия Трауберг и Дороти Коллинз - сестры по духу: Коллинз выкидывает из оригинала при републикации (без оговорок, естественно) и целые абзацы, и отдельные фразы посреди абзаца (в первую очередь как раз ядовитые - чтобы поглаже было), и просто заменяет отдельные слова на более гладкие. Например: в оригинале removal короля, в републикации death короля. В оригинале: я бранил аристократию and shall continue to do so (till I am sacked); - в републикации till I am sacked опущено: надо бы поглаже. В оригинале the Bedford Park lady - в републикации the artistic lady (видимо, чтоб никто не решил, что это эвфемизм для чего-то нехорошего, - а это и вправду не он); в оригинале сказано, что король был популярнее of Mr. Asquith or Mr. Balfour, в републикации - что он был популярнее of any politician, нечего читателю голову ломать, что это за Асквит такой; полностью опущен большой прогон ГКЧ о том, как безобразно и атеистично одеваться в знак траура в черное (вот этот: Mere black might seem a more fitting dress for devils than for Christian mourners, except that the mourning dress of devils would (I suppose) be blue. There is something almost atheistic about such starless and hueless grief; it seems not akin to distress, but to despair) - видно, Коллинз решила дразнить публику поменьше и не выставлять автора таким ненадобным шпынем, каким он выставлял себя сам; вовсе снята фраза "even one who doubted whether the King deserved his popularity would be forced to admit that he had it"... Полностью опущен огромный начальный пассаж первого эссе. И много еще в таком духе.

Уж не считать ли, что подтасовки, непрерывно и "искренне" осуществлявшиеся в уме автора, создавали вокруг него поле, в котором его издатели и переводчики шли уже на сознательные подтасовки и вранье? Бог весть. Как бы то ни было, привожу оба эссе в том оригинальном виде, как они были опубликованы в 1910 г. в "Лонд. илл. нов".

1. May 28, 1910. The Death of Edward VII. Death has struck the ancient English Monarchy at the very moment when that Monarchy was about to re-enter history. For the first time, certainly for a hundred years — probably for three hundred — the personality of the King of England profoundly mattered to English politics; at that moment the personality has been changed. In our whole present public crisis the appeal was to the Monarchy : the Monarchy was actually reviving while the Monarch was dying. To any patriotic man this fact must be even more impressive than the disappearance of a great and popular personality. We may be of those who, like Lord Rosebery and others, feel the present crisis quickening towards political chaos; who feel the ship of State to be flying faster and faster down a flood ; and who hear from far in front the faint but ceaseless thunder of the rapids of revolution. We may be of that other and much sadder school (with whose sincerity I, for one, have sometimes been bitterly haunted) which thinks that England is drifting, not on to the breakers, but into a backwater: that we have before us not seething democracy, but stagnant oligarchy; that the English ship of State is not heading for the storms of the French or the Irish Channel, but only for the dead aquarium and open tanks of Venice. But, whatever be the order of our hope or fear, we can all feel that England is in a crisis, and that England is taking a turn. We all know that the King mattered mightily to the turn that it took; and we all know that the King is dead. These are the things that make men feel that fierce coincidence which is almost superstition. Superstition, indeed, might have much to say touching this national tragedy, if people took superstition quite seriously. But it is the whole mistake to suppose that people do take it seriously. Superstitions are a sort of sombre fairy-tales that we tell to ourselves in order to express, by random and realistic images, the mystery of the strange laws of life. We know so little when a man will die that it may well be sitting thirteenth at a table that kills him. Superstitions really are what the Modernists say that dogmas are : mere symbols of a much deeper matter, of a fundamental and fantastic agnosticism about the causes of things. Thus; in our present public bereavement, anyone seriously anxious to prove that "the heavens themselves blaze forth the deaths of Princes" could say with unanswerable truth that we were lit this year by the same monstrous meteor that is said to have hung over the fall of Caesar and the last fight of Harold. Thus, again, those attached to mediaeval popular fancies may point out that this year Good Friday fell on Lady Day, 3 as it did when the Black Plague was eating the nation; or in that darker war with Joan of Arc, in which our England was disgraced both in defeat and victory. But there are very few of such seriously superstitious persons. Healthy humanity uses such signs and omens as a decoration of the tragedy after it has happened. Caesar was right to disregard Halley's Comet; it had no importance until Caesar had been killed. Rationalists, who merely deride such traditions, fail by not feeling the full mass of inarticulate human emotion behind them. On the very night that King Edward died, it happened that the present writer experienced some of those trivialities that can bring about one’s head all the terrors of the universe. The shocking news was just loose in London, but it had not touched the country where I was, when a London editor attempted to tell mc the truth by telephone. But all the telephones in England were throbbing and thundering with the news; it was impossible to clear the line; and it was impossible to hear the message. Again and again I heard stifled accents saying something momentous and unintelligible; it might have been the landing of the Germans or the end of the world. With the snatches of this strangled voice in my ears I went into the garden and found, by another such mystical coincidence, that it was a night of startling and blazing stars — stars so fierce and close that they seemed crowding round the roof and tree-tops. White-hot and speechless they seemed striving to speak, like that voice that had been drowned amid the drumming wires. I know not if any reader has ever had a vigil with the same unreasoning sense of a frustrated apocalypse. But if he has, he will know one of the immortal moods out of which legends rise and he will not wonder that men have joined the notion of a comet with the death of a King.

But besides this historic stroke, this fall of a national monument, there is also the loss of a personality. Over and above the dark and half-superstitious suggestion that the fate of our country has turned a corner and entered a new epoch, there is the pathetic value of the human epoch that has just closed. The starting-point for all study of King Edward is the fact of his unquestionable and positive popularity. I say positive, because most popularity is negative; it is no more than toleration. Many an English landlord is described as popular among his tenants, when the phrase only means that no tenant hates him quite enough to be hanged for putting a bullet in him. Or, again, in milder cases, a man will be called a popular administrator because his rule, being substantially successful, is substantially undisturbed; some system works fairly well and the head of the system is not hated, for he is hardly felt. Quite different was the practical popularity of Edward VII. It was a strictly personal image and enthusiasm. The French, with their talent for picking the right word, put it best when they described King Edward as a kind of universal uncle. His popularity in poor families was so frank as to be undignified; he was really spoken of by tinkers and tailors as if he were some gay and prosperous member of their own family. There was a picture of him upon the popular retina infinitely brighter and brisker than there is either of Mr. Asquith or Mr. Balfour. There was something in him that appealed to those strange and silent crowds that are invisible because they are enormous. In connexion with him the few voices that really sound popular, sound also singularly loyal. Since his death was declared there have already been many written and spoken eulogies; one that sounded indubitably sincere was that uttered by Mr. Will Crooks. If you dig deep enough into any ancient ceremony, you will find the traces of that noble truism called democracy, which is not the latest but the earliest of human ideas. Just as in the very oldest part of an English church you will unearth the level bricks of the Romans, so in the very oldest part of every royal or feudal form you will unearth the level laws of the Republic. In that complex and loaded rite of Coronation, which King Edward

underwent, and his successor must soon undergo, there is a distinct trace of the ancient idea of a King being elected like a President. The Archbishop shows the King to the assembled people and asks if he is accepted or refused. Edward VII, like other modern Kings, went through a ritual election by an unreal mob. But if it had been a real election by a real mob — he would still have been elected. That is the really important point for democrats.

The largeness of the praise of King Edward in the popular legend was fundamentally due to this, that he was a leader in whom other men could see themselves. The King’s interest in sport, good living, and Continental travel was exactly of the kind that every clerk or commercial traveller could feel in himself on a smaller scale and in a more thwarted manner. Now, it emphatically will not do to dismiss this popular sympathy in pleasure as the mere servile or vulgar adoration of a race of snobs. To begin with, mere worldly rank could not and did not achieve such popularity for Ernest Duke of Cumberland or Alfred Duke of Edinburgh or even for the Prince Consort; and to go on with mere angry words like snobbishness is an evasion of the democratic test. I fancy the key to the question is this; that, in an age of prigs and dehumanized humanitarians, King Edward stood to the whole people as the emblem of this ultimate idea — that however extraordinary a man may be by office, influence, or talent, we have a right to ask that the extraordinary man should be also an ordinary man. He was more representative than representative government; he was the whole theme of Walt Whitman — the average man enthroned.

His reputation for a humane normality had one aspect in which he was a model to philanthropists. Innumerable tales were told of his kindness or courtesy, ranging from the endowment of a children’s hospital to the offer of a cigar, from the fact that he pensioned a match-seller to the mere fact that he took off his hat. But all these tales took the popular fancy all the more because he himself was the kind of man to share the pleasures he distributed. His offer of a cigar was the more appreciated because he offered himself a cigar as well. His taking off his hat was the more valued because he himself was by no means indifferent to decent salutations or discourteous slights. Philanthropists too frequently forget that pity is quite a different thing from sympathy; for sympathy means suffering with others and not merely being sorry that they suffer. If the strong brotherhood of men is to abide, if they are not to break up into groups alarmingly like different species, we must keep this community of tastes in giver and received. We must not only share our bread, but share our hunger.

King Edward was a man of the world and a diplomatist; but there was nothing of the aristocrat about him. He had a just sense of the dignity of his position; but it was very much such a sense as a middle-class elective magistrate might have had, a Lord Mayor or the President of a Republic. It was even in a sense formal, and the essence of aristocracy is informality. It is no violation of the political impartiality of the Crown to say that he was, in training and tone of mind, liberal. The one or two points on which he permitted himself a partisan attitude were things that he regarded as common-sense emancipations from mere custom, such as the Deceased Wife’s Sister Bill. Both in strength and weakness he was international; and it is undoubtedly largely due to him that we have generally dropped the fashion of systematically and doggedly misunderstanding the great civilization of France. But the first and last thought is the same: that there are millions in England who have hardly heard of the Prime Minister, and never heard of Lord Lansdowne, to whom King Edward was a picture of paternal patriotism; and in the dark days that lie before us it is, perhaps, just those millions who may begin to move.

II

June 4, 1910 The Character of King Edward. The calamity of the King's removal was unofficially acknowledged almost before it was officially acknowledged. The people were prompter in mourning than the officers of state in bidding them mourn and even one who doubted whether the King deserved his popularity would be forced to admit that he had it. The national mourning — taken as a whole, of course — is all the more universal for being irregular, all the more unanimous for being scrappy or even intermittent. Armies of retainers clad in complete black, endless processions of solemn robes and sable plumes, could not be a quarter so impressive as the cheap black band of a man in corduroys or the cheap black hat of a girl in pink and magenta. The part is greater than the whole. Nevertheless, the formal side of funeral customs, as is right and natural, is already engaging attention. Sir William Richmond, always prominent in any question of the relation of art to public life, has already sketched out a scheme of mortuary decoration so conceived as to avoid the inhuman monotony of black. He would have a sombre, but still rich, scheme of colour, of Tyrian purple, dim bronze, and gold. Both artistically and symbolically, there is much that is sound in the conception. Mere black might seem a more fitting dress for devils than for Christian mourners, except that the mourning dress of devils would (I suppose) be blue. There is something almost atheistic about such starless and hueless grief; it seems not akin to distress, but to despair. Indeed, Sir William Richmond, consciously or unconsciously, is in this matter following an ecclesiastical tradition. The world mourns in black, but the Church mourns in violet — one of the many instances of the fact that the Church is a much more cheerful thing than the world. Nor is the difference an idle accident; it really corresponds by chasms of spiritual separation. Black is dark with absence of colour; violet is dark with density and combination of colour; it is at once as blue as midnight and as crimson as blood. And there is a similar distinction between the two ideas of death, between the two types of tragedy. There is the tragedy that is founded on the worthlessness of life; and there is the deeper tragedy that is founded on the worth of it. The one sort of sadness says that life is so short that it can hardly matter; the other that life is so short that it matters for ever.

But though in this, as in many other matters, it is religion alone that retains any tradition of a freer and more humane popular taste, it may well be doubted whether in the present instance the existing popular taste should not be substantially gratified, or, at least, undisturbed. King Edward was not the kind of man in whose honour we should do even beautiful things that are in any sense eccentric. His sympathies in all such matters were very general sympathies; he stood to millions of people as the very incarnation of common-sense, social adaptability, tact, and a rational conventionality. His people delighted in the million snapshots of him in shooting-dress at a shooting-box, or in racing clothes at a race-meeting, in morning-dress in the morning or in evening-dress in the evening, because all these were symbols of a certain sensible sociability and readiness for everything with which they loved to credit him. For it must always be remembered in this connexion that masculine costume is different at root from feminine costume — different in its whole essence and aim. It is not merely a question of the man dressing in dull colours or the woman in bright; it is a question of the object. A Life Guardsman has very splendid clothes; an artistic lady may have very dingy clothes. But the point is that the Life Guard only puts on his bright clothes so as to be like other Life Guards. But the Bedford Park lady always seeks to have some special, delicate, and exquisite shade of dinginess different from the dinginess of other Bedford Park ladies. Though gleaming with scarlet and steel, the Life Guard is really invisible. Though physically, no doubt, of terrific courage, he is morally cowardly, like nearly all males. Like the insects that are as green as the leaves or the jackals that are as red as the desert, a man generally seeks to be unseen by taking the colour of his surroundings, even if it be a brilliant colour. A female dress is a dress; a male dress is a uniform. Men dress smartly so as not to be noticed; but all women dress to be noticed — gross and vulgar women to be grossly and vulgarly noticed, wise and modest women to be wisely and modestly noticed.

Now, of this soul in masculine ‘good form’, this slight but genuine element of a manly modesty in conventions, the public made King Edward a typical and appropriate representative. They like to think of him appearing as a soldier among soldiers, a sailor among sailors, a Freemason at his Lodge, or a Peer among his Peers. For this reason they even tolerated the comic idea of his being a Prussian Colonel when he was in Prussia; and they took a positive pleasure in the idea of his being a Parisian boulevardier when he was in Paris. Since he was thus a public symbol of the more generous and fraternal uses of conventionality, we may be well content with a conventional scheme of mourning; especially when in this case, as in not a few other cases, the conventional merely means the democratic. King Edward’s popularity was such a very popular kind of popularity that it would be rather more appropriate to make his funeral vulgar than to make it aesthetic. It is true that legend connects his name with two or three attempts to modify the ungainliness and gloom of our modern male costume; but he hardly insisted on any of them, and none of them was of a kind specially to satisfy Sir William Richmond. The aesthetes might perhaps smile on the notion of knee breeches; but I fear that brass buttons on evening coats would seem to them an aggravation of their wrong. Even where King Edward was an innovator, he was an innovator along popular and well-recognized lines; a man who would have liked a funeral to be funereal, as he would have liked a bail to be gay. We need not, therefore, feel it so very inappropriate even if in the last resort the celebrations are in the most humdrum or even jog-trot style, if they satisfy the heart of the public, though not the eye of the artist.

And yet again, in connection with those aspects of the late King which may be and are approved on more serious and statesmanlike grounds (as, for instance, his international attitude towards peace), this value of a working convention can still be found. It is easy to say airily, in an ethical textbook or a debating club resolution, that Spaniards should love Chinamen, or that Highlanders should suddenly embrace Hindus. But, as men are in daily life, such brotherhood is corrupted and confused, though never actually contradicted. It is the fundamental fact that we are all men; but there are circumstances that permit us to feel it keenly and other circumstances that almost prevent us from feeling it at all. It is here that convention (which only means a coming together) makes smooth the path of primal sympathy, and by getting people, if only for an hour, to act alike, begins to make them feel alike. I have said much against aristocracy in this column, and shall continue to do so till I am sacked, but I will never deny that aristocracy has certain queer advantages, not very often mentioned. One of them is that which affects European diplomacy: that a gentleman is the same all over Europe, while a peasant or even a merchant, may be very different. A Dutch gentleman and an Irish gentleman stand on a special and level platform; a Dutch peasant and an Irish peasant are divided by all dynastic and divine wars. Of course, this means that a peasant is superior to a gentleman — more genuine, more historic, more national; but that, surely, is obvious. Nevertheless, for cosmopolitan purposes, such as diplomacy, a gentleman may be used — with caution. And the reason that has made aristocrats effective as diplomatists is the same that made King Edward effective; the existence of a convention or convenient form that is understood everywhere and makes action and utterance easy for everyone. Language itself is only an enormous ceremony. King Edward completely understood that nameless Volapuk or Esperanto on which modern Europe practically reposes. He never put himself in a position that Europe could possibly misunderstand, as the Kaiser did by his theocratic outbursts, even if they were logical; or the Tsar by his sweeping repressions, even if they were provoked. Partly a German, by blood, partly a Frenchman, by preference, inter-married with all the thrones of Europe and quite conscious of their very various perplexities, he had the right to be called a great citizen of Europe. There are only two things that can bind men together; a convention and a creed. King Edward was the last, the most popular, and probably the most triumphant example of Europe combining with success upon a large and genial convention. Tact and habit and humanity had in him their final exponent in all the Courts, reviews, race-courses, and hotels of Christendom. If these are not enough, if it is not found sufficient for Europe to have a healthy convention, then Europe must once more have a creed. The coming of the creed will be a terrible business.

Классификация фоновой музыки для бизнеса: популярные жанры

Классификация фоновой музыки для бизнеса: популярные жанры  Девушка, которая танцует (Часть 2)

Девушка, которая танцует (Часть 2)  Выставка «Я»

Выставка «Я»  Немного бетонных шишечек

Немного бетонных шишечек  Космонавт № 3

Космонавт № 3  Что входит в идеальный школьный комплект перед началом года

Что входит в идеальный школьный комплект перед началом года  Тролль спрятался

Тролль спрятался  4000 км, 80 дней

4000 км, 80 дней  Кто такой Цербер

Кто такой Цербер